CIArb Features

The emergence of the “Pubs Code Adjudicator”: An analysis of the Pubs Code Regulations 2016

25 Aug 2020

Dr Jed Meers*

This article is a detailed interrogation of a new Janus-faced creature in British arbitration: the “code adjudicator”. Focusing on the Pubs Code Adjudicator and the underpinning Pubs Code Etc Regulations 2016, the dual-role the adjudicator plays – at once an arbitrator and a regulator – and the powers and problems evident in its first years in operation are evaluated. This use of statutory arbitration, coupled with regulatory oversight, to intervene in a sector dominated by historic power imbalances shows promise, but persistent problems need addressing. In a time of historic challenges to the pub sector, never has addressing the power-imbalance between tied-tenants and their pub-owning companies been more significant.

Keywords: Statutory arbitration, pubs code adjudicator, small businesses, landlord and tenant, dispute resolution, English law, regulator.

The full article and references can be found here.

1. Introduction

2013 saw a new creature emerge in British arbitration: the “code adjudicator”. The Groceries Code Adjudicator – established under its namesake Act in 2013 – was followed by the Pubs Code Adjudicator – established under the Small Business, Enterprise and Employment Act 2015. Both are Janus-faced. On the one hand, they discharge an arbitration function in disputes between parties with an inherent power-imbalance: the supplier and their supermarket buyers, or the tied-pub tenant and their pub-owning company. On the other, they discharge a regulatory function: presiding over a statutory code, issuing advice and guidance, and imposing financial penalties for non-compliance.

This article is a detailed interrogation of the second of these adjudicators, the “Pubs Code Adjudicator” (PCA). Here, I seek to provide a detailed overview of their powers and a critique of the operation of the Pubs Code to date. This statutory intervention in the pub market seeks to address an historic power imbalance between tied-pub tenants and the far larger, better resourced pub-owning companies. However, in practice, the Pubs Code Adjudicator has struggled to align their arbitration and regulatory roles and their underpinning powers have been deficient, underutilized or unclear. Recent cases – Punch Partnerships Ltd v Highwayman Hotel (Kidlington) Ltd. and Punch Partnerships (PTL) Ltd v Jonalt Ltd – attest to the difficulty the PCA and its appointed arbitrators have faced in interpreting their powers under the Code. As we enter a period in which the pub sector faces some of the greatest challenges to its viability in its modern history, this article: (i) provides an assessment of the Pubs Code Adjudicator’s powers, (ii) details the rights of tied-tenants, and (iii) critiques problems in the operation of the code and the exercise of dual-functions by the adjudicator. In doing so, this is the first sustained critique of the “code adjudicator” model.

The analysis in five sections. The first contextualises the discussion to follow by providing context on the “beer tie” and the Pubs Code intervention. The second and third deal with the Pubs Code Adjudicator’s function as an arbitrator of the rights of tied tenants (to a rent assessment/proposal and “market rent only” offer, respectively). The fourth section deals with the PCA’s function as a regulator, before the fifth critiques the function of the code thus far.

2. Tied Pubs as a legal battleground

At its core, the Pubs Code is the use of statutory arbitration and regulation to constrain a power imbalance between tied-tenants and the largest pub-owning companies. Pubs have long been a battleground between their leaseholders – the pub landlords, often also living in the property – and the freeholders, traditionally the breweries themselves and more recently the modern “Pub Owning Company” (PubCo). These lease agreements often carry what is known as the “beer tie”, though its reach is far broader than beer. The proposition is simple: in return for reduced rent and business support, the tied tenant’s procurement is constrained under the lease through a contractual arrangement of exclusive supply.

These restrictions on procurement – known as the “wet rent” – require the tenant to purchase beer and almost always wines, spirits, soft drinks and other supplies from the owner of the establishment. These exclusive supply arrangements both come at a higher cost, with the Office for Fair Trading estimating that the price of beer is on average 30% higher under a tie (with other organisations arguing the differential is far higher), and heavily constrain the products available to the tenant, effectively restricting purchasing power to a finite list and precluding purchasing drinks or other tied products (such as food) on the open market.

The higher prices and controls resulting from the tie are set against a cheaper than market rent for the property and the provision of other services. This is more than just business acumen: a fundamental principle of competition law within such vertically integrated models is that exclusive purchasing obligations – which function clearly to restrict competition – are offset by countervailing benefits. Indeed, a series of references by brewers to the EU Commission have dealt specifically with this issue, concluding that such ties can be “more than offset by quantifiable countervailing benefits”.

There are two important points to note in how this offset occurs under the beer tie. First, this cheaper rent (the so-called “dry rent” against the “wet rent” above) is ordinarily calculated not by reference to the market rate for the property, but instead a division of the estimated turnover and profit a competent publican can fashion, known as the “fair maintainable trade” (FMT). In practice, this calculation relies on detailed income and expenditure forecasts, resulting in an overall estimated profit to be divided between the tenant and the PubCo. Ordinarily, this is between 35% to 65%, known as the “divisible balance”. The resulting figure is then reflected in the “dry rent” for the property, with the tied tenant carrying the associated risks of failing to meet the projected turnover. As argued by Higgins et al, this “risk transfer” from the pub company to the pub tenant is a defining feature of the vertical supply chain in the British pub sector. The bottom-line of these calculations is that tied publications earn substantially less than their non-tied counterparts, with the IPPR highlighting that 46% of tied publications earn less than £15,000 per year – more than double the rate for non-tied publicans.The role of arbitration in overseeing this complex process of dry rent calculation is an important component of the Pubs Code which this article returns to.

Second, a key argument put forward by PubCos is that these leases contain the valuable provision of business services and advice that help to offset the costs associated with the “wet rent” and form part of the reductions to turnover reflected in higher “dry rent”. In a competition law sense, these are “special commercial or financial advantages” from which tied tenants benefit, including training, public relations provision, marketing and business advice. In practice, these too have been criticised for being of little benefit when set against the far higher overall costs associated with the tie, or being difficult to quantify. The assessment of these commercial and financial advantages – particularly the extent to which they are capable of being fully-costed and itemised in the calculation of the “dry rent” – is another source of contestation between tied tenants and their PubCo.

3. The Adjudicator as Arbitrator: Mechanisms for Reviewing Rent

The raison d’etre of the Pubs Codes is founded in two animating principles specified in Part IV of the Small Business, Enterprise and Employment Act 2015. The design of the underpinning Pubs Code Regulations 2016, the powers of the Pubs Code adjudicator and their decision-making in adjudications revolve around s.42(3), which states the intervention should be consistent with:

(a) the principle of fair and lawful dealing by pub-owning businesses in relation to their tied pub tenants;

(b) the principle that tied pub tenants should not be worse off than they would be if they were not subject to any product or service tie.

These two principles are returned to frequently in both the Pubs Codes themselves and in decisions by the adjudicator in arbitrations. As the Pubs Adjudicator puts it in Edward Anderson v Marstons PLC:

All of the issues in the case should be considered in the light of the overriding principles found in section 42 of the 2015 Act because they are the starting point to understanding the Pubs Code and the statute that enabled it…The core Code principles are at the heart of the statutory purpose behind the establishment of the Pubs Code regime…

The Pubs Code is enacted under these principles, taking shape through The Pubs Code etc Regulations 2016 and The Pubs Code (Fees, Costs and Financial Penalties) Regulations 2016. These regulations apply to pub-owning companies with more than 500 pubs in their estate – currently six PubCos and at least 11,500 tied pub tenants in total. As far as the adjudicator’s dispute settlement role is concerned, the regime is a creature of statutory arbitration and falls under the framework outlined in s.94 Arbitration Act 1996.

Given the historical problems with tied pubs and the ethos of the Pubs Code, a clear focus of the 2016 regulations – presided over by the Pubs Code Adjudicator – is inevitably on the calculation of rent. If tied tenants are not to be “worse off than they would be if they were not subject to [a] tie”, assessing the calculation of the “dry rent” and the imposition of other terms in any tied lease (i.e. the “wet rent”) are a fundamental component of giving effect to the regulations “overriding principles”. Indeed, the Pubs Code Adjudicator has underscored that “the overarching principle from which flows consideration” of rent, “is the principle of fair and lawful dealing by pub-owning businesses in relation to their tied pub tenants”.

The 2016 Regulations introduce two routes for a review of the rent: “rent proposals” and “rent assessments”. The former deal with proposals for rent under a new tenancy (or varying an existing tenancy) and the latter with the assessment of rent in an existing tenancy. If either is triggered, the PubCo must provide a “Rent Assessment Proposal” that meets certain requirements (detailed below) and – if the tied tenant considers there to be problems – the process and contents of these proposals can be referred for arbitration.

In practice, the underpinning Pubs Code provides three ways for a tied tenant to access an assessment of the rent payable. First, at the point at which a rent review takes place in the course of the tenancy. This is an automatic requirement for the PubCo: where there is a contractual review of the rent in the tenancy, they must issue a compliant rent assessment proposal. This does not include increases as a result of inflation or other changes to the rent that do not arise from a rent review (e.g. where rent is changed to accommodate a new benefit received from the PubCo). Second, because there has not been a rent review (or a rent assessment proposal) in the last five years. Third, at the point at which there is a significant price increase in the tie (e.g. the cost of a product or service increases significantly) or there is a “trigger event”, where there is an external occurrence that results in the expected trade of the pub to be significantly decreased. In each of these scenarios, the tied tenant has a right to request a “rent assessment proposal”; procedural obligations (such as serving correct notices within a given timescale) then apply.

I. Addressing information asymmetry

For both “rent assessments” and “rent proposals”, the bulk of the duties imposed by the Pubs Code Regulations Etc 2016 deal with addressing the significant lack of bargaining power possessed by tied tenants in comparison to the PubCos. PubCos are well-versed in thousands of rental negotiations and will have access to specialist in-house advice and the resources to secure outside consultancy (for instance, on the assessment of local market conditions and so on). In comparison, the tied tenant themselves does not have access to the same resources or wealth of experience built by PubCos, indeed, they are likely to be facing their first such negotiation unrepresented. In common with most secondary legislation intervening in such imbalances, a key policy aim is tackling the information asymmetry existing in contract between the small (often lay) party and the larger company.

These requirements are laid out in Schedule Two of the Pubs Code, and are almost all to do with the provision of key information to inform negotiations over rent – such as the PubCo disclosing the method used to calculate the rental offer and providing a fully itemised profit/loss account. Table One provides a summary of these: paragraphs five to ten of the schedule all introduce requirements for the profit/loss forecast, and the remaining paragraphs introduce other free-standing requirements to disclose information (e.g. providing a list of relevant and irrelevant matters for the negotiations).

Table One: A summary of the specified information detailed in Schedule Two Pubs Code Regulations 2016

|

Requirements imposed under Sch.2 Pubs Code Regulations 2016 |

|||

|

Free-standing information requirements |

Requirements tied to the profit and loss forecast |

||

|

Paragraph |

Summary |

Paragraph |

Summary |

|

One |

The method used to calculate the rent, inc. justifications for the sources of information used. |

Five |

An itemised profit and loss forecast for the first 12 months of the forecast rent period. |

|

Two |

An outline of the procedure to be followed during rent negotiations. |

Six |

To provide the figures in para.5 net of VAT and games machine taxes. |

|

Three |

A list of (ir)relevant matters for the negotiations. |

Seven |

Any variance between the figures in para.5 and publicly available costs of running a pub must be explained. |

|

Four |

The cost of service charges for the pub over the last three years. |

Eight |

The information provided in para.5 must be sufficiently detailed/explained so that the tenant can understand the basis of the figures arrived at. |

|

Eleven |

Any information in respect of making an new agreement (outlined in Sch.1) – if it hasn’t already been provided – should also be provided. |

Nine |

The information under para.5 must be accurate (if historical data) and reasonable (if projected data). |

|

Twelve |

A timetable for the negotiation, including dates by which any other information will be made available to the tenant. |

Ten |

Calculations under para.5 must detail volume of alcohol in respect of which any excise was paid the last three years. |

This focus on the provision of information and transparency of the negotiations is found elsewhere in the code. Most notably, for all meetings between the PubCo and the tied tenant, an appointed business development manager at the PubCo must make “appropriate notes of any discussions” with the tied tenant in relation to negotiations under the Code, including for rent proposals and assessments, and provide these to the tied tenant within 14 days. Indeed, Marston PLC’s failure to provide complete notes of discussions with a tenant – and providing these 9 days late – has been the subject of Pubs Code Adjudicator arbitration decision against them.

As with the rest of the PubsCode, the Adjudicator has – in the course of a series of published arbitrations – offered guidance on how to interpret these duties. The information requirements imposed on the PubCos detailed in Schedule Two have been interpreted through the prism of the principle of “fair and lawful dealing”. It is not enough that PubCos disclose the listed documents in their own right, there is an onus on them to furnish these with explanations where required to assist the tied-tenant’s understanding. As the Pubs Code Adjudicator puts it in one such arbitration:

Consistency with the principle of fair and lawful dealing between a POB and a TPT in my view requires that obligations be complied with in a transparent and accessible manner, that enables a TPT to access their rights under the Code [53].

It is not enough, therefore, that a PubCo provides the list of information detailed in the schedule: it must also be “easily accessible and understood by tenants”. In further efforts to aid such transparency and to provide a consistent standard to evaluations, rent proposals and rent assessments must also be completed in accordance with Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors’ guidance and be accompanied by written confirmation from a chartered surveyor to confirm this. The relevant guidance details, in broad terms, the process of calculating the fair maintainable operating turnover and profit that defines the approach to determining tied-pub “dry rent” detailed above. Though, importantly, this guidance was last issued in December 2010 (and was already subject to criticism shortly after its publication).

II. The Anderson decision: Tangible effects on the assessment of rent

These requirements to disclose information are more than simply about securing transparency in PubCo decision-making and allowing the tied-tenant to negotiate in a more informed manner. They can have tangible effects on the level of rent set for a property. This is for two key reasons. First, all of the requirements within Schedule Two and elsewhere in the Pubs Code outlined above are to be read alongside the Pubs Code’s underpinning principles – in particular, the “the principle of fair and lawful dealing by pub-owning businesses in relation to their tied pub tenants”. As a result, the Adjudicator has underscored in arbitration awards that to avoid “commercial imbalance” and secure consistency with this principle, the “onus is upon the POB to demonstrate compliance” (notwithstanding that treatment of the burden of proof issue by the High Court does not accord with this; see the discussion of Jonalt below). Second, the PCA has a wide-ranging discretion to determine the reasonableness of the contents of any such rent assessment or proposal and of the information (or reasons for not providing information) provided by the PubCo under Schedule Two.

Perhaps the best example to date of the far-reaching implications of the Schedule Two requirements can be seen in Edward Anderson and Marstons PLC. Here – among many other failures – the PubCo had not accounted for sediment in cask ale when formulating their rent assessment proposal, only general wastage of 2.5% (for instance, as a result of line cleaning). Schedule Two requires PubCos to, inter alia, provide information on: (i) the volume of alcohol purchased from the PubCo by the tied tenant in the last three years, (ii) the volume of alcohol in respect of which duty was paid, and (iii) an estimate of how much beer and cider will not be sold in the forecast period (due to wastage or being unfit to sell). The PubCo asserted that they had “no reason to believe that the volume of alcohol in respect of which duty was paid…differs from the volume…purchased by the Claimant”, and simply applied a 2.5% wastage allowance across all draught products, without distinguishing wastage from sediment/unsellable beer. This is despite the PubCo maintaining their own sediment lists across beers internally.

The PubCo’s position led to the nonsensical result that the tied-tenant’s rent is calculated on the basis that there are 72 pints of sellable beer within cask, whereas – when accounting for sediment – there are 68 or fewer. This had considerable ramifications on the total estimated turnover for a pub, and therefore inflated the rent. Here, the Pubs Code Adjudicator concluded in an arbitration award that the PubCo had acted in breach of the requirements of the Code and inconsistently with the principle of fair and lawful dealing by failing to provide the information and account for the role of sediment. This decision, arising from these obligations to disclose information, is likely to have far reaching consequences across the PubCo sector where the calculation of rent without reference to sediment levels is widespread.

4. The Adjudicator as Arbitrator: The “Market Rent Only” Option

The Pub Code’s flagship intervention is the so-called “Market Rent Only” option. This is (in theory, if problematically in application) a free-standing right of a tied-tenant to trigger a free-of-tie offer from their PubCo, where – instead of being subject to a tied arrangement with all of its associated costs (“wet rent”) but with a lower rent (“dry rent”) – they simply pay the market rent for the property. It is a backstop to the Pub Code’s animating principle that no-tied tenant should be worse off than if they were not subject to a tie: an option for all tied tenants to leave their current arrangement go free of the tie if they so choose.

A tied-tenant can request an MRO proposal from their PubCo in response to set of “triggers” detailed in the regulations. This process is underpinned by s.43 Small Business, Enterprise and Employment Act 2015, which states, inter alia:

(4) A tenancy or licence is MRO-compliant if—

(a) taken together with any other contractual agreement entered into by the tied pub tenant with the pub-owning business in connection with the tenancy or licence it—

(i) contains such terms and conditions as may be required by virtue of subsection (5)(a),

(ii) does not contain any product or service tie other than one in respect of insurance in connection with the tied pub, and

(iii) does not contain any unreasonable terms or conditions, and

(b) it is not a tenancy at will.

(5) The Pubs Code may specify descriptions of terms and conditions—

(a) which are required to be contained in a tenancy or licence for it to be MRO-compliant;

(b) which are to be regarded as reasonable or unreasonable for the purposes of subsection (4).

Under the power in s.43(5), the only other regulations that detail the form and content of a compliant proposal are found in Regulations 30 and 31 of the Pubs Code. These set out, respectively, terms that are required in the proposed tenancy (e.g. that it is for a period at least as long as the remaining term of the existing tenancy), and those terms that are considered to be unreasonable (e.g. that they are terms which are which are not common terms in agreements between landlords and pub tenants who are not subject to product or service ties).

Given the lack of prescription, there is both a broad range of possible compliant leases that can satisfy the principle of an MRO-compliant offer and a wide discretion afforded to both the PubCo and the Pubs Code Adjudicator in determining the compliance of such offers. The only organising concept that the Pubs Code supplies is that of “reasonableness”: both in broad terms within s.43(4) of the 2015 Act, and in determining those “terms which are not common terms in agreements between landlords and pub tenants who are not subject to product or service ties” under Reg.31(2)(c) Pubs Code Etc Regulations 2016.

I. A “stocking requirement” is not a tie

Importantly, however, the regulations distinguish “tied” arrangements and a broader class of leases that contain what are known as “stocking requirements”: a “new concept” introduced under the Pubs Code. This distinction is not dealt with in the Pubs Code itself, but is instead a function of how “tied pubs” are defined within the underpinning Small Business, Enterprise and Employment Act 2015. Section 68(7) details that:

(7) The contractual obligation is a stocking requirement if—

(a) it relates only to beer or cider (or both) produced by the landlord or by a person who is a group undertaking in relation to the landlord,

(b) it does not require the tied pub tenant to procure the beer or cider from any particular supplier, and

(c) it does not prevent the tied pub tenant from selling at the premises beer or cider produced by a person not mentioned in paragraph (a) (whether or not it restricts such sales).

As a result, although MRO-compliant proposals cannot carry terms that amount to a “tie”, they can carry these “stocking requirements” providing that meet they meet the definition in s.68(7) and are otherwise “reasonable” under s.43(4) of the 2015 Act. As the explanatory note to the 2015 Act underscores, this allows a PubCo to “impose restrictions on sales of competing beer and cider in line with prevailing competition law, so as long as the restrictions do not prevent the tenant from selling such products.” As was underscored in passing of the amendment leading to this change, the basis of these “stocking requirements” is to help brewers “protect their route to market” for beer and cider, providing that tenants are “able to buy the brewer’s products from any source”.

In the course of MRO proposals, evidence from Pubs Code Adjudicator arbitrations suggests that some PubCos have sought to stretch significantly the meaning of a “stocking requirement” under s.68(7). Arbitrations have featured PubCos prohibiting the sale of any keg brands without prior consent, introducing requirements to carry products not produced by the landlord or its group undertakings (such as creating stocking requirements from breweries in which the landlords owns shares), and the requirement to carry a high percentage of keg or cask Landlord brands (e.g. at least 60% of carried products).

All such attempts have fallen outside of the definition of a “stocking requirement”. The Pubs Code Adjudicator has clarified the ambit of such terms in a series of arbitrations, considering that:

“In any particular case the simple and correct way to approach the matter is to ask “is this product beer or cider produced by another person?”. If the answer is yes, and if the lease term prevents its sale, then the term does not fall within the definition of a stocking requirement.”

This reading of the definition is part of the fundamental intent behind the legislation creating this concept of a “stocking requirement” in the first place. As noted by the PCA in an arbitration award, it is necessary to “distinguish the opportunity to protect the brewer POB’s route to market for products it brews”, which is the legislative intent, with the “opportunity to increase the brewer POB’s route to market for those products”, which is not.

II. Vehicle for an MRO

A key question that has emerged in practice is what the correct vehicle for a compliant MRO offer should be? Whether the MRO takes the form of a deed of variation to the current lease or is imposed as a new lease altogether can have considerable financial implications for the tied tenant. In the course of arbitrations referred to the Pubs Code Adjudicator, there is evidence of PubCos introducing significant barriers to entry through the use of new leases as opposed to deeds of variation, in particular: (i) variations to rent payment increments or significant rent in advance, (ii) requiring large deposits to be paid on entering into the new lease, (iii) the tied-tenant being liable for additional taxes (i.e. Stamp Duty Lamp Tax), and (iv) insisting on the payment of terminal dilapidations.

This latter practice is particularly egregious. The function of terminal dilapidation covenants is to ensure that where a tenant fails to “yield up the premises in good repair”, the landlord’s cost of remedying their breach can be met. The amount a landlord can claim is therefore limited to the extent to which the value of their interest in property is reduced by the disrepair. Where the current tenant is staying put, to insist on the payment of terminal dilapidations on the first day of a new MRO lease – which in one such arbitration was to the sum of £116,000, referred to by the tied-tenant as “exorbitant/imaginary” – both takes a hammer-blow to any tied-tenant’s cash flow or resources and prolongs (likely costly) negotiations on the extent of such terminal dilapidations. As a result, they are in danger of rendering any MRO-offer entirely illusory.

The Pubs Code Adjudicator has given short shrift to this practice in a series of arbitrations. Landlords should not be using these entry costs as an “adversarial weapon” to deter or prevent tied-tenants from accessing a meaningful MRO option. As underscored by the Adjudicator in one such arbitration:

“As the MRO should be reasonably accessible to the TPT, entry costs should not represent an unreasonable barrier. Parliament intended that there should be a genuine choice to the TPT whether to go free to tie or remain tied.”

The underpinning regulations themselves, however, are silent on whether a compliant MRO has to be in the form of a new lease or a deed of variation. The use of word “tenancy” throughout the Pubs Code Etc Regulations 2016 could apply to both the grant of a new tenancy and a deed of variation. Likewise, if the legislation’s drafters had anticipated only deed of variations being used, then the protections outlined in Reg.31(4) Pubs Code Etc Regulations 2016, which effectively prevent an MRO compliant offer from removing the tied-tenants ability to renew their lease in most circumstances, would not be necessary.

As a result, the Pubs Code Adjudicator’s role is not to require PubCos to use a specified format, but instead to assess the “reasonableness” of an MRO offer as a whole (including its format) and therefore its compliance. There are two strands to this logic. First, the terms of the MRO offer cannot be “unreasonable” under s.43(4)(iii) Small Business, Enterprise and Employment Act 2015. This is both individually and collectively. Assessing the format of the MRO is therefore part of assessing the reasonableness of the terms of the offer as a whole. Second, if a PubCo only offers a MRO by virtue of a new lease, this in effect an applied condition in its own right that is subject to the reasonableness test. Therefore, the position of the Pubs Code and its underpinning legislation is that the “MRO vehicle and terms by the POB…must be demonstrably reasonable.”

5. The Adjudicator as Regulator: PUBCO Duties and Powers of Investigation

The other side of the Janus-face is the Pubs Code Adjudicator’s significant regulatory responsibility. In terms of its scope, this outstrips its adjudicative role. The Small Business, Enterprise and Employment Act 2015 confers broad-ranging investigatory and enforcement powers on the adjudicator. Where they have “reasonable grounds” to suspect that a PubCo has not complied with the Code, they can trigger a wide-ranging investigative power, including the ability to enforce the disclosure of documents from a PubCo and solicit evidence from any sources they consider appropriate.

This process is underpinned by the power to impose large fines and direct binding recommendations or the publication of material. If, following an investigation, the Adjudicator concludes a PubCo has failed to comply with the Pubs Code, they can impose a penalty of up to 1% of a PubCo’s annual turnover. For the largest PubCos – such as EiGroup, with a turnover in 2018/19 of £724 million – this has the potential to stretch into millions of pounds. In the guidance issued by the Pubs Code Adjudicator, they refer broadly to adopting the “Macroy principles” in the assessment of any such penalty: chiefly, using sanctions proportionally to change the behavior of the offender and deter future non-compliance.

Despite these broad-ranging powers – and the significant scope of the Adjudicator’s regulatory responsibility across the whole of the Pubs Code – there has been, at the time of writing, only one such investigation triggered by the Adjudicator. This launched on 10th July 2019 (more than three years after the imposition of the Code) and focuses on the use of non-compliant stocking requirements by one PubCo, Star Pubs & Bars Limited. This is yet to conclude.

The Office of the Pubs Code Adjudicator has recognised that this important part of their function has been heavily neglected in the first few years of the Code’s operation. In their response to the Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy’s review, they noted how their “dual statutory functions have frequently exerted pressures on each other.” Elsewhere, the Adjudicator has noted their intention to “mov[e] decisively” away from managing individual arbitrations, and instead to focus on “regulatory interventions to increase the pace of behavioural and cultural change and to embed compliance.”

The PCA’s regulatory role has also suffered from a lack of clarity on the meaning of some aspects of the underpinning Pubs Code regulations. Indeed, as the PCA notes themselves in response to the statutory review, “it is highly unusual for the regulator to have to make decisions on what the law means ahead of taking regulatory action on that law.”

6. Problems

After the first few years of the Pubs Code’s life, significant problems persist. Some limitations have been referred to above, but a series of distinct issues warrant further attention here: (i) the interaction with the Landlord & Tenant Act 1954, (ii) the burden of proof, (iii) powers to direct the inclusion of lease terms, (iv) access to arbitration awards, and (v) considerable delays and poor outcomes. Each of these will be deal with in turn.

I. Interaction with the Landlord & Tenant Act 1954

As a statutory intervention concerned with the rights of tied-tenants, the Pubs Code inevitably has consequences on the legal relationship between landlord and commercial tenant. In most cases, tied-tenants benefit from the application of protections in the Landlord & Tenant Act 1954 which, inter alia, limit the reasons for which a landlord can refuse the renewal of a lease. The MRO rights under the Pubs Code are exercised as a distinct process, not as part of lease renewals governed by the 1954 Act: the Civil Procedure Rules were amended following the introduction of the Pubs Code to allow the court to delay any renewal proceedings pending the outcome of the MRO process.

However, a key blind spot emerges in the interaction between these two processes. As outlined above, there are a series of “triggers” for the MRO-option, one of which is the renewal of a tenancy – either following notice from a PubCo, or a request by the tied-tenant. PubCos can and do, however, issue hostile notices to refuse renewal on the basis that they intend to “occupy the holding for the purposes…of a business to be carried on by him therein” Such notices allow PubCos to instead transfer properties into their managed estate. This is not without cost to the PubCo. Opposing renewal on this ground will require the payment of compensation – perhaps as much as two times the ratable value of the property – and can be contested by the tied-tenant by, for instance, interrogating the validity of the business plan for such an owner-managed approach.

II. Burden of proof

A key concern of the court in Jonalt was where the burden of proof lies in determining the “reasonableness” of an MRO-lease term: is the onus on the PubCo to demonstrate that a term is reasonable, or does it fall on the tied-tenant? Here, the PubCo had proposed a “stocking requirement” in their MRO-lease requiring the tied-tenant to stock “at least 60%” of landlord brands (in this case, products from the Heineken portfolio). The tied-tenant argued that this stocking requirement was unreasonable and counter-offered a 20% threshold. Neither party submitted factual or expert evidence in the course of the arbitration, and – as a consequence – the arbitrator considered that the PubCo had not demonstrated the stocking requirement was reasonable and ordered the inclusion of the 20% threshold in the MRO-offer.

On appeal, the High Court determined that – in placing the burden of proof on the PubCo – the arbitrator’s award suffered from a “serious irregularity” under s.68 Arbitration Act 1996. The court noted that “on the normal rules of the burden of proof, the onus lay on the tenant to establish the breach alleged” and there was nothing in the Pubs Code to infer otherwise.

This departs from the position in a series of arbitrations presided over by the PCA and sits oddly alongside the whole MRO-process. The Pubs Code functions by placing a requirement on the PubCo to issue a compliant (and therefore “reasonable”) MRO-offer: there is a statutory duty on them to do so. It follows that the PubCo should be able to demonstrate how this MRO-offer is compliant, not for the tenant to demonstrate how it is not compliant.

III. Powers to direct the inclusion of terms

Both Highwayman Hotel and Jonalt deal with the powers of an arbitrator appointed under the Pubs Code to direct that specific terms are included or excluded from an MRO lease offer. In Highwayman Hotel the PubCo sought to argue that the PCA’s assumption that they can impose a five-year lease period is both outwith their powers under the regulations and an unlawful interference with the PubCo’s fundamental right to dispose of their property as they choose (under the first part of the first protocol, A1P1). The PCA argued that their powers under Reg. 33(2) Pubs Code Regulations 2016 were permissive and broad-ranging:

(2) Where—

(a) a matter is referred to the Adjudicator under regulation 32(2)(a) to (c); and

(b) the Adjudicator rules that the pub-owning business must provide a revised response to the tied pub tenant,

the pub-owning business must provide that response within the period of 21 days beginning with the day of the Adjudicator's ruling or by such a day as may be specified in the Adjudicator's ruling.

The court disagreed. Although the Pubs Code provides the PCA with the power to require a PubCo to issue a revised response, they could not determine the terms within that response: that is to be left to the PubCo, and then subject – if needed – to further arbitration. The court noted that where the Pubs Code does provide powers to interfere with the PubCo’s property rights, it is explicit in doing so, pointing to the power to appoint an independent assessor (who in turn can determine the market rent for the property) under regs. 36, 37 and 59 as one such example. The permissive language in reg.33 was not enough to “empower the arbitrator to interfere with the economic and property interests of the parties” – for the court to be satisfied that such a power exists, it needed to be more clearly expressed in the underpinning legislation.

This position sits oddly alongside the Pubs Code’s founding principles detailed under s.42(3) Small Business, Enterprise and Employment Act 2015, namely that:

(3) The Secretary of State must seek to ensure that the Pubs Code is consistent with—

(a) the principle of fair and lawful dealing by pub-owning businesses in relation to their tied pub tenants;

(b) the principle that tied pub tenants should not be worse off than they would be if they were not subject to any product or service tie.

Any interpretation of the powers conferred to the PCA or appointed arbitrators under the Code need to be interpreted with these two principles at front of mind. Indeed, the judgment promises a return to the “overarching intention of the 2015 Act and the Pubs Code…” when dealing with this issue, but such analysis is not forthcoming.

The position of the court in Highwayman – endorsed fully in Jonalt – has considerable practical implications. Stripping away the ability of the PCA to impose terms where (as in this case) a protracted cycle of arbitration exists, could lead to larger, far better resourced PubCos gaming the arbitration process to exhaust the resources of tied tenants. Indeed, the court accepts that their position poses “a risk of further delay, cost and attrition involved in repeated offers and arbitration” that “might harm the Tenant more than the Landlords”. It is difficult to find an issue that bites more on the underpinning “principle of fair and lawful dealing” in s.42(3) Small Business Enterprise and Employment Act 2015, yet this principle does not feature in the court’s statutory interpretation of the reg.33 power.

IV. Access to arbitration awards

In common with most other forms of arbitration, awards issued by the PCA or their appointed arbitrators are commercial sensitive and can contain information parties may not wish to disclose publicly or to competitors. The Office of the PCA has, however, committed to publishing arbitration awards (even if subject to redaction) to ensure that “tied tenants and pub companies an equal level of understanding as to how the Code is being applied in individual arbitrations”. At the time of writing, a total of 18 awards relating to MRO disputes and 8 awards relating to non-MRO disputes (for instance, rent assessments and proposals) have been published. This compares to a total cumulative case load for the PCA of 262 awards from 21/07/2016 to 31/12/2018.

The publication of arbitration awards has been interrogated more generally in this journal before. As Zlatanska argues, there is a significant inequality of arms generated between “‘one-shotters’ and ‘repeat players’”, with the former having “by default, limited or no information about how to proceed and what to expect from the arbitration process”. For a statutory intervention intended to address the power imbalance between large PubCos (most of whom deal with large numbers of referrals to the PCA, and therefore have access to their own bank of awards and other knowledge) and tied-tenants (where, for most, they will deal with only one such process in respect of their own pub), this inequality of arms in access to knowledge is particularly acute. At present, although the current published awards provide helpful insight into the PCA’s interpretation of the code, PubCos continue to benefit not only from greater financial resources than their tied-tenants, but a greater knowledge resource too.

V. Delay and outcomes

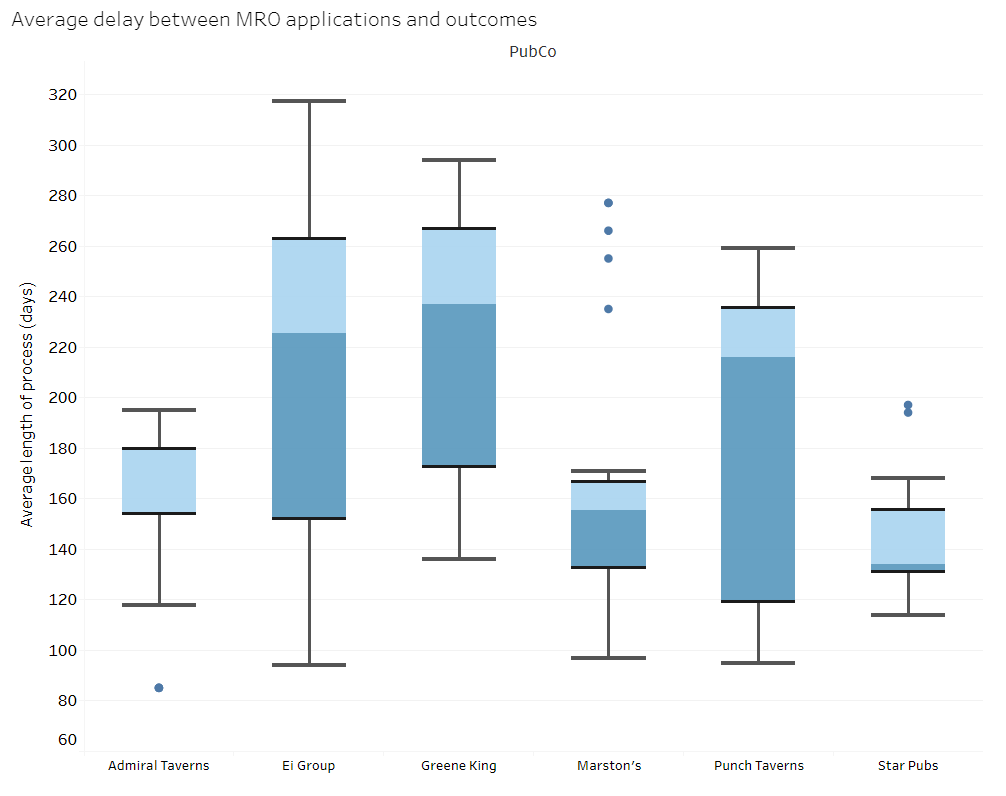

Finally, it is worth noting both the considerable delay in MRO processes and the likely outcomes of triggering an MRO-notice. In short, negotiations are long (taking the best part of year and often more) and rarely conclude with a free-of-tie pub. Figure One details boxplots of average delays between MRO notices and outcome, broken down by PubCo.

Figure One: Average delay between MRO application and outcome.

There is clearly significant variation between PubCos, with negotiations for Greene King lasting median of 237 days, to Star Pubs lasting a median of 134 days. The average across all PubCos is 164 days. Compared with the tight time turnarounds within the regulations – with PubCo responses required within 28 days and default negotiation being 56 days – these far longer average time periods suggest that negotiations are liable to be significantly longer than envisaged under the Pubs Code itself.

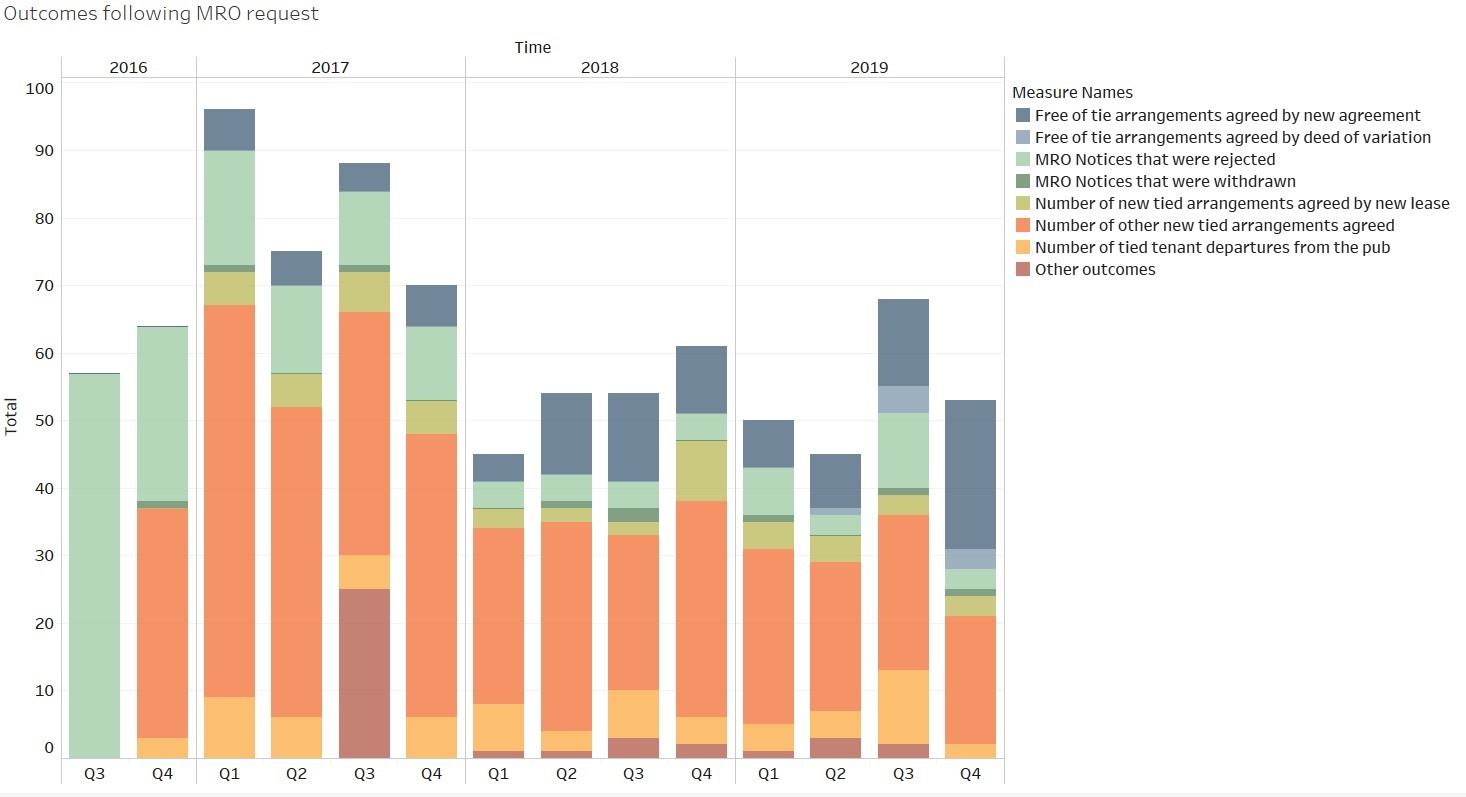

These delays between MRO application and outcome should be read alongside the data on what the parties agree. Figure Two details the outcomes that follow an MRO request, broken down by year and quarter.

Figure Two: Outcomes following an MRO request.

These data show that free-of-tie arrangements are relatively rare. Nearly half of outcomes are tenants entering into new tied arrangements with the PubCo (418 instances from quarter 3 in 2016 until quarter 4 in 2019) or entered into a new tied lease (51 instances). Whereas free-of-tie arrangements accounted for 110 outcomes over the same period. The PubsCode is not, therefore, a wholesale transfer of tied-leases to free-of-tie leases. It is instead exerting an effect on negotiations between tied parties, even if they may not conclude with tenants exercising their statutory right, or may indicate that “market rent” itself may be proving difficult to agree.

7. Conclusion

This article has focused on a detailed assessment and critique of one form of “code adjudicator” – the PCA. In a sector long plagued by power imbalances between pub tenants and pub owners, the role played by this hybrid arbitrator and regulator will be a central factor in the survival of a large part of the pub sector. According to British Beer and Pub Association survey data, more than one in three establishments fear for their survival in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic.

In this context, problems in the operation of the Pubs Code Etc Regulations 2016 and the PCA are set into sharp relief. A lack of clarity about the extent of power conferred under statutory arbitration within the Code, as reflected in Highwayman Hotel and Jonalt, have blunted the power of the PCA or appointed arbitrators to impose terms on awards and have placed the burden of proof on tied-tenants. Gaps within the code allow PubCos to navigate around its protections, including by pulling tied-pubs into their owner-managed estates.

More fundamentally, the “code adjudicator” model rests on an interaction between hybrid regulatory and arbitration roles. In its early years, the PCA was heavily focused on the latter: managing a high arbitration case load and seeking to interpret the protections of the Code through its arbitration practice. This has come at the neglect of its regulatory role. The Office of the PCA has launched only a single investigation under its regulatory powers, despite widespread evidence of non-compliance within the sector.

The analysis in this article suggests that – although the PCA is a welcome intervention in a market that has suffered from an evergreen problem of power-imbalance – more needs to be done to clarify and strengthen the power of the PCA, and to encourage the full use of their statutory powers. The forthcoming (and long awaited) statutory review of the Pubs Code Regulations Etc provides an opportunity to begin to address these issues at a moment of historic challenge for the pubs sector.